- Recognize signs that the universal support in a learning environment needs to be evaluated.

- Define targeted supports.

- Understand who needs targeted supports.

- Describe how environmental supports, sensory supports, scripted stories, and peer supports can address concerning behaviors.

Learn

Know

Imagine a crowded banquet hall filled with one hundred people. The DJ cues up a popular song that most people in the group know. As you watch the crowd, you notice around 70 people have joined the dance right away. They know the moves and seem to enjoy themselves. Approximately 25 people still linger around the edge of the dance floor. They wait until a friend motions for them to join, or they break off in small groups and practice the moves a little more slowly until they feel ready to join. With a little encouragement and support, these 25 also seem to enjoy themselves. Now that 95 people are dancing, you notice that a small number of people seem to be making different choices. Three people are moving wildly out of step with everyone else. They are bumping into others and trying to knock them down. Two have sat down on the dance floor and don’t seem interested in joining the dance. The 95 dancers seem to move away from these five to avoid getting hurt or hurting them. Sometimes, these five dancers are asked to leave the dance floor. Or imagine instead that a group of caring and skilled dance instructors are able to join in and provide guidance, so everyone, all 100 people, can participate together in different ways.

Child and youth programs are a lot like this crowded dance floor. Your program environment, relationships, and curriculum are like the inviting dance floor and a good DJ: around 70 to 80 percent of children and youth will join in right away and have a great experience. Another 20 to 25 percent will need some extra directions and patience before they feel ready, but with the right supports they, too, will thrive in the program. However, in any group, approximately 5 percent of children and youth will make choices that concern you or that threaten safety. Without intervention, these children will not thrive.

If we apply this dance floor ratio to a typical group size of 20 children or youths, you can expect 14 children will thrive with just the typical universal supports of a high-quality program and engaging curricular programming. Five children will need targeted supports to help them build social, communication, self-care, or coping skills. One child, on average, will need intensive supports and a highly individualized plan designed specifically to address that child’s behavioral and social-emotional needs.

These numbers, of course, are not absolute. In any group of children or youths, you may have a larger or smaller number of children who would benefit from targeted or intensive supports. As a rule, though, if a large number of children or youths in your classroom or program seem to need targeted support or intensive intervention, this is a clue that you should carefully evaluate how well your universal supports are working for the children. In other words, if a large number of children or youth in your classroom are exhibiting challenging behaviors it may be an indication that you need to adjust your environment, curriculum, or expectations. It is likely that all children benefit from careful attention to relationships, behavioral expectations, clarity of routines, and engaging curricular experiences. Think of this ratio like a pyramid. Your pyramid should not be upside down: if every child needs intensive individualized supports, it likely means there is a problem with the foundation of your pyramid. Start adjusting your universal supports until it becomes clear whose behavior is truly unresponsive to high-quality, responsive care.

Targeted Social Emotional Supports

Who Needs Targeted Supports?

Think about the 25 or so people in the banquet hall who needed the encouragement of a friend or extra practice before joining the rest of the group on the dance floor. In the context of a child care program, these are the children who will benefit from targeted supports. These children may demonstrate inconsistent abilities or need a slight boost to be able to carry out a task or routine. For example, after several months in the classroom, Brady, a preschooler, is sometimes able to complete the morning routine of putting his name tag on the “Who’s Here Today” board, putting his folder in the bin, and choosing a book from the library area of the room. Other times, Brady struggles to start the routine or throws his backpack and coat on the floor before running to an activity. The team has noticed that Brady has this same concerning behavior of not following through with multistep routines, during other parts of the day. Brady, and children like him, may benefit from a targeted support so they can learn to consistently follow routines and rules.

What are targeted supports? Targeted supports are tools, activities, or experiences that help children and youth learn important skills so they can fully participate in their environment. Targeted supports typically promote social, communication, self-care, and coping skills and are used in addition to foundational strategies, such as supporting responsive interactions. Examples of targeted supports are listed in figure 1.

Figure 1

Targeted Supports

Examples of Targeted Supports

Four specific types of targeted supports for children who need help beyond universal supports include environmental supports, sensory supports, scripted stories, and peer supports.

Environmental Supports

All behavior is influenced by the places and routines in which it occurs. The first thing adults can try when they are concerned about behavior is to thoughtfully adjust the environment or routines. The ultimate goal is to make sure the bottom levels of the pyramid that you learned about in Lessons One through Three are in place and working well. There are several questions adults should ask one another as they plan environmental supports (adapted from Simonsen et al., 2015):

- Is the physical design of the classroom or program space meeting the needs of the child?

- Are the routines predictable and clear?

- Are positive expectations for behavior posted, taught, and talked about frequently? Examples include expectations like, “Be safe, be respectful, be kind.”

- Are children and youth actively supervised? Do adults proactively and positively supervise the child whose behavior is of concern?

- Are there many opportunities for children or youth to be actively engaged (doing interesting things, participating in challenging and meaningful experiences)?

- Do adults notice and comment on positive child or youth behaviors?

- Are transitions minimized and are children and youth actively engaged during transition times?

- Do adults use reminders before a behavior is likely to occur (i.e., “it’s almost time to clean up. Remember, when you hear the signal, put your toys away…”)

- When challenging behaviors occur, do adults respond consistently by telling children what to do instead of what not to do?

- Do adults have positive relationships with all children? Are there frequent positive interactions about the interests, experiences, and feelings of the children or youth?

The Virtual Lab School Positive Guidance course Lessons One and Two have more detailed descriptions about environmental strategies that help children and youth manage their own behaviors.

Use the questions above to identify specific changes that might help a child’s concerning behavior. For example, Brady’s teaching team might develop a picture schedule to remind him of what to do. They may create an arrival mini-schedule so he has a visual reference for the routine:

https://challengingbehavior.org/pyramid-model/behavior-intervention/teaching-tools/

They may also create first-then boards to help make routines simpler and to ensure adults use consistent directions:

Finally, adults may focus on the ways they respond to Brady when challenging behaviors occur. They may focus on reminding him about appropriate behaviors. They may want to avoid words like No, Stop, and Don’t, and praise or encourage him when they see positive behaviors. The Communication is Key document from the National Center on Pyramid Model Interventions can be a helpful reminder for Brady’s team: https://challengingbehavior.cbcs.usf.edu/docs/ttyc/TTYC_B_CommunicationIsKey.pdf

Sensory Supports

All people uniquely experience the sensations in their environments, and some children may need support to cope with the sensory aspects of their environments. There are children who may become upset by loud noises or the feeling of a tag on their clothing. Others may have a hard time focusing on what’s going on in their environment when, for example, there is a buzzing fluorescent light in the room. These are just a few examples of how our sensory experiences can affect our behavior. Sometimes children’s sensory related behaviors are concerning, and sometimes how children experience their sensory environment prevents them from following a routine or expectation. You should understand that children do not choose to have these difficulties, or their resulting behaviors. However, it may be helpful to use these general strategies for children who need targeted sensory support:

- A quiet corner or chair within the classroom, but away from the more active areas, available to children who benefit from the option of removing themselves from stimulating environments. Letting children know about this option can prevent a concerning or challenging behavior.

- Teach children sensory-based solutions. For example, a young toddler screams after dipping her hands in yogurt. A caregiver can say, “When your hands get messy, we use a paper towel to make them clean,” while wiping off the child’s hands. Though this child may not be able to ask for a paper towel yet, the caregiver models the language to problem-solve the situation and a solution to her need.

- Plan ahead so children are prepared to encounter an environment that may be challenging for them. A child who becomes very upset when exposed to bright light is about to go outside with her class on a bright, sunny day. The caregiver shows the child, by looking out the window together, that it is very sunny and also points out a shady spot where she might like to play.

Scripted Stories

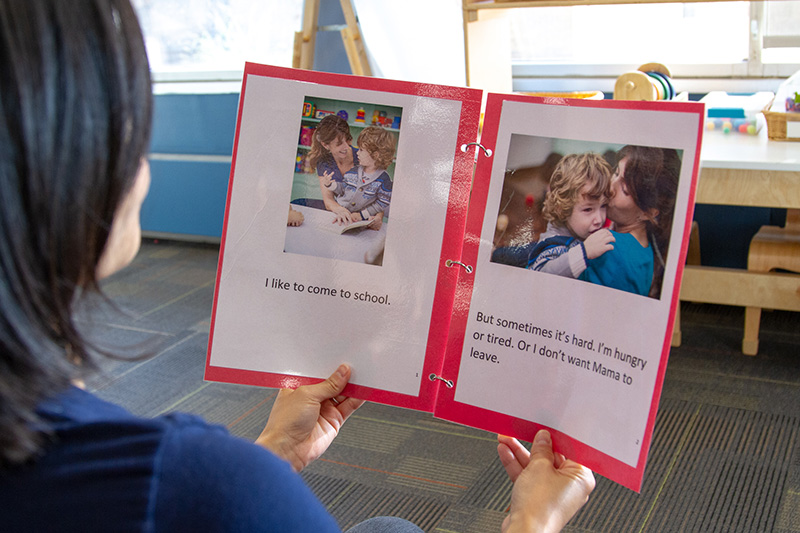

For many children and youth whose behavior concerns adults, scripted stories can be a simple and effective tool to teach the rules or expectations of common social interactions. Scripted stories are usually short. They are written from the child’s or youth’s point of view using “I,” “me,” and “my.” The plot of the story focuses on the specific routine or situation that the child or youth struggles with. Let’s consider Brady again:

Based on informal observation, the team felt that Brady’s behavior might improve with all routines and become more consistent if they could smooth out the first transition of the day: arrival. They decided to write a scripted story about drop-off. They would ask Brady’s family to read it at home in the morning or give it to him to look at in the car. They would also have a copy at the program, and a staff member would read it with him and other children who need this support first thing each morning. The scripted story went something like this:

I like to come to school.

But sometimes it’s hard. I’m hungry or tired. Or I don’t want Mama to leave.

I feel sad or angry or lonely.

When I feel sad, angry, lonely, or hungry, I can tell a grown up.

They have ideas for fun things to do!

When I get to my classroom, I wash my hands.

Then I can get breakfast or I can play with a special box of toys at the game table.

I have fun when I play, and my mama and teachers are proud of me!

They print the story out with one line per page, and add pictures of Brady in the classroom doing the things described on each page. They make two copies and put them in small binders. They laminate the pages to make them more durable. They give one book to Brady’s family, and one stays in the classroom. Each morning for a week, Carla welcomes Brady as soon as she sees him at the door and says, “Hi Brady! I’m so happy to see you. Let’s read your special book and start our day.” She makes sure to give him lots of positive attention while reading the book and encourages him every time he follows the steps of the book. After one week, they begin using the book less, but they pull it out whenever he has a difficult morning or is running late.

Although the example above is from early childhood, scripted stories can also be effective in school-age and youth programs. For youth over age 8, staff might consider using a comic book–style scripted story. Youth may also write their own stories in the form of simple to-do lists or day-planner agendas. Adults would simply check in with the youth to go over the agenda or checklist and spend a few moments having a positive interaction. Youth may also enjoy creating their own reminders of problem-solving processes. This may be on a small card the youth keeps in their pocket or a space in the program area where the youth can go to review problem-solving steps.

Peer Supports

Peers can play a major role when there are concerns about a child’s or youth’s behavior. Behavior is communication, and this means behavior is often social. The child or youth may communicate with his or her peers through behavior. Their behavior may say:

- I want to play with you.

- I don’t want to play with you.

- I need space.

- I’m stressed out.

- I don’t understand what you want from me.

- I want what you have.

When there is a concern about a child’s or youth’s behavior, take time to observe their interactions with peers. Consider these questions:

- Who does the child or youth spend the most time with?

- Who does the child have positive interactions with?

- Who does the child have negative or strained interactions with?

- Who would you consider to be their friend?

- Who tends to be involved in strained or difficult interactions with them?

- Who are the children or youth in the program who may be good role models? Who gets along with others, has age-appropriate social skills, shares interests with the child or youth, and typically makes good choices?

When you have a sense of the child’s or youth’s relationships with peers, you can use this information to plan peer supports. Typical peer supports are the buddy system, friendship activities, and designing peer mediation for school-age youth.

Use the Buddy System

The buddy system can be an effective way to promote appropriate behavior and build relationships among children and youth (Lentini, Vaughn, & Fox, 2005; 2008)

For older children or youth, buddy systems can be used in ways that are age-appropriate. For example, staff may work with youth to develop a plan for two children to ride together on the bus each day. A youth may go over their agenda or behavior checklist with a friend at the start of each program day, or two peers may make a plan to check each other’s homework.

Design Friendship Activities

Adults and peers can help children and youth learn new skills. These new skills should be matched with the function of the behavior. For example, if the function of the child’s behavior is to get access to materials that peers are playing with, the adults may plan specific opportunities for children to practice asking to play or taking turns. Here are a few examples:

- Friendship Table: an area has a toy or game that can only be played with two people. When a child/youth chooses to go to that area, they must ask a peer to play with them.

- Reading Partner: children/youth invite a partner to read with them. They take turns being the reader and the listener. This can be used in preschool (children “read” the pictures) through early school-age.

- Partner Dice: Attach pictures or names of children to a cube. Have children roll the dice to choose a partner to invite to play.

Offer Peer Mediation Programs

School-age children can learn to resolve their own conflicts and regulate their own behavior. Peer mediation is a strategy in which youth learn specific strategies for problem identification, negotiation, and mediation. Typically, a group of youths are taught how to be peer mediators. When social problems or behavior problems occur, peer mediators work with the two youths to identify the problem and come to a solution. Adults support this process and help the youth navigate these interactions. A detailed manual about peer mediation for school-age children is available on the Educational Resource Information Center at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED438193.pdf (or see the full PDF attached below).

See

Some children may need targeted supports to learn routines, develop new skills, and engage in relationships with others. Targeted supports can be used for a short or transitionary period of time, or some children may need them ongoingly. Have you used targeted supports before? If so, how did this help the child? Are there children or youth you currently care who may benefit from targeted supports?

Targeted Supports

Do

If children in your care struggle to follow routines and expectations or have concerning or challenging behavior, consider the following questions and ideas:

- Think about how all the children are able to follow classroom routines and expectations. Are most children getting it? Or does it feel like nearly everyone is struggling? How long have children had to learn the routines and expectations?

- Check your environment to make sure you are doing everything you can to prevent the challenging behavior. Determine whether small adjustments to the space, schedule, or routines might help.

- Consider that all children have different sensory experiences, and some need more support in this area than others.

- Reflect on your relationship with the child. Are you effective at engaging with the child? Do you show encouragement and joy toward the child and their unique qualities?

- Consider writing scripted stories and using visual schedules and if-then charts to make expectations clear for the child.

- Get peers involved. They can be buddies, play partners, or peer mediators.

Explore

As you read about targeted supports that may help the behavior of children and youth, remember to think about why it is important to follow the Pyramid Model steps when you recognize that a child or youth needs more help. Read the National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations' fact sheet about young children with challenging behavior and answer the questions listed in the Challenging Behaviors Reflection handout.

Apply

Use the tip sheets to learn how to create a Visual Schedule and a First-Then Board. These tools can be used to provide targeted support for children and youth who need help learning routines and expectations.

Glossary

Demonstrate

Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning. http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu/

Dunlap, G., Wilson, K., Strain, P., & Lee, J. (2013). Prevent-Teach-Reinforce for young children. Baltimore, MD: Paul. H. Brookes.

Dunlap, G., Iovannone, R., Kincaid, D., Wilson, K., Christiansen, K., Strain, P., & English, C. (2010). Prevent-Teach-Reinforce: The school-based model of individualized positive behavior support. Baltimore, MD: Paul. H. Brookes.

Lentini, R., Vaughn, B. J., & Fox, L. (2008). Creating teaching tools for young children with challenging behavior [CD-ROM], Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Technical Assistance Center on Social Emotional Intervention for Young Children.

Pluess, M., Assary, E., Lionetti, F., Lester, K. J., Krapohl, E., Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (2018). Environmental sensitivity in children: development of the highly sensitive child scale and identification of sensitivity groups. Developmental Psychology, 54(1).

National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations: https://challengingbehavior.cbcs.usf.edu/

Pyramid Model Consortium: http://www.pyramidmodel.org/

Rush, D. D., & Shelden, M. L. L. (2011). The early childhood coaching handbook. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Simonsen, B., Freeman, J., Goodman, S., Mitchell, B., Swain-Bradway, J., et al. (2015). Supporting and responding to behavior: Evidence-Based classroom strategies for teachers. https://www.pbis.org/common/cms/files/pbisresources/Supporting%20and%20Responding%20to%20Behavior.pdf

U.S. Army, Child, Youth and School Services. (n.d.). Operational guidance for behavior support.

Wahman, C.L., Pustejovsky, J.E., Ostrosky, M.M., & Santos, R.M. (in press). Examining the effects of social stories on challenging behavior and prosocial skills in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education.